‘Resilient’ feels like the ‘phrase du jour’. People are throwing ‘resilience’ about like confetti, but I’m not totally convinced we are all speaking the same language (let alone understanding what we are on about).

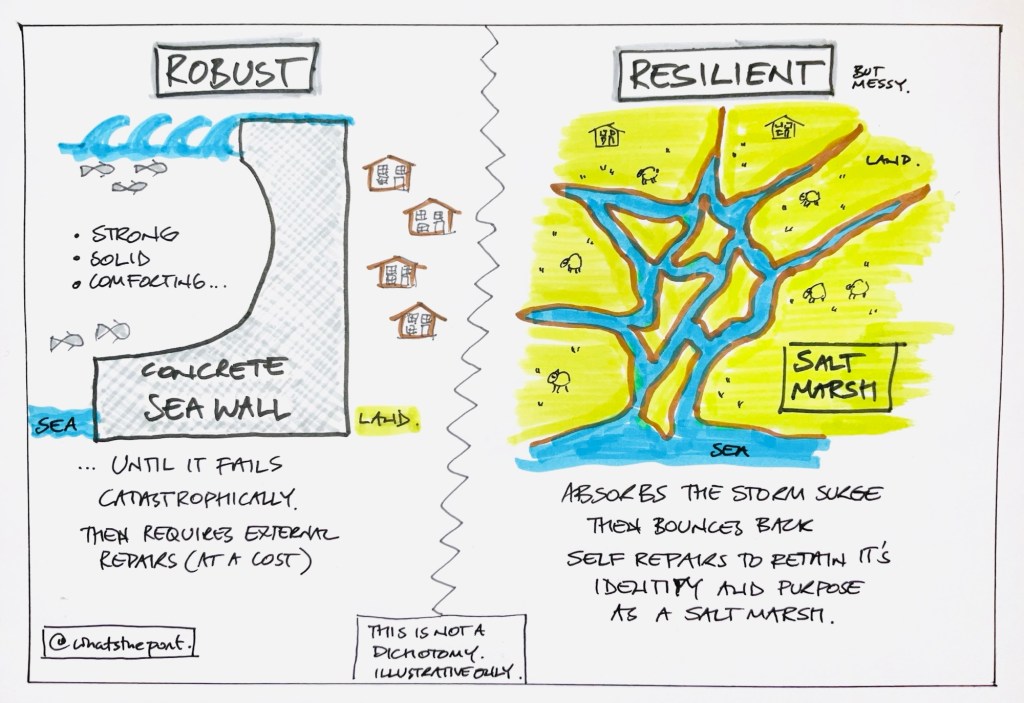

Personally, I’m in the ecological resilience ‘be more salt marsh’ camp. However, what I’m hearing amongst the confetti is lots of solid, concrete robustness; the stuff of sea walls. Nothing wrong with either, it’s just worth recognising the difference.

First, the tale of a Salt Marsh. Cwm Ivy existed as a salt marsh for thousands of years before becoming my favourite salt marsh.

Twice every 24 hours Loughor Estuary salty water would wash it’s way up muddy channels. Then at low tide it would flow back out of Burry Pill, supporting the plant and animal life that makes a salt marsh.

During severe weather events it would absorb what nature had to thrown at it, and then settle back into being a salt marsh. Changes to it’s characteristics might have happened, but overall it retained it’s purpose and identity as a salt marsh.

Cwm Ivy was probably doing salt marsh things over 4,500 years ago, when the Neolithic Tribes of South Wales erected King Arthur’s Stone (Megalithic tomb with a 25 ton capstone) on the high ground draining to Burry Pill.

It was still a salt marsh in 1485 when King Henry VII’s troops (on their way to fight at the Battle of Bosworth) took a 60 mile detour to visit King Arthur’s Stone .

However, sometime during the 17th century land owners built a sea wall across Cwm Ivy to keep out the salt water. For the next 300 years it functioned as a fresh water marshy pasture, according to this project factsheet from Natural Resources Wales.

Then in 2014 the inevitable happened. The sea wall failed during the winter storms and salt water rushed in. Quickly the freshwater habitat deteriorated. The owners, The National Trust, decided not to repair the sea wall, and allow Cwm Ivy to return to being a salt marsh.

By the winter of 2017 a fully functioning wildlife-rich tidal salt marsh had returned. Cwm Ivy Salt Marsh doing what a salt marsh should do. Letting the tide in and out, absorbing floods and storms and being part of a thriving ecosystem. Although, it hasn’t been to everyone’s liking, particularly those who used the sea wall as a footpath.

Historical note: In the late 1980’s I spent quality time dragging myself through muddy salt marshes, as part of a team measuring the impact of nutrient loading (sewage discharges) on marine algae. Close personal time with a salt marsh gives you an appreciation of their resilience.

Resilience comes in different flavours. The robust (sea wall) and resilient (salt marsh) illustration I’ve used is something Dave Snowden has spoken about . I keep returning to it as something to get the point across that resilience can be looked at from different perspectives.

One of the other sources on resilience I’ve returned to goes back to ‘dragging myself through salt marsh mud’ times. The Canadian ecologist C.S.Holling has done a huge amount of work on the resilience of natural systems. I think this has wider application to organisational life.

If you want to learn about C.S.Holling’s work I recommend reading ‘Engineering Resilience versus Ecological Resilience’ from the 1996 book Engineering Within Ecological Constraints.

Some points I’ve taken from the chapter:

- Engineering resilience is characterised by maintaining the ‘efficiency’ of a system.

- There will be a focus on standardisation, a few reliable things and little diversity.

- There will be limited flexibility.

- This can lead to failure when conditions unexpectedly change.

- A robust sea wall seems to fit these characteristics (or indeed a highly efficient, stable team following tightly defined process guidance and churning out widgets).

- Ecological resilience is characterised by maintaining the ‘survival’ (purpose and identity) of the system.

- There will be diversity, lots of different bits doing different things.

- But they all contribute to the overall purpose.

- Efficiency isn’t the overall objective and some individual parts will be vulnerable.

- In response to environmental changes some parts will thrive and some decline, but overall the system is flexible and it survives.

- A salt marsh seems to fit these characteristics (or indeed a messy and not particularly efficient group of people involved in organisational improvement, innovation, R&D etc).

So, What’s the PONT?

- Resilience feels like the ‘phrase du jour’, being thrown around like confetti. But do we speak the same language?

- Sea walls are robust, salt marshes are resilient. A useful reminder to stop an think about what we mean when we say ‘resilient’?

- Absorbing an unexpected shock and ‘bouncing back’, can cause a change, but retaining your purpose and identity is an important characteristic to survive in a volatile world. Be more salt marsh.

Leave a comment