How we make decisions and remember things as society depends on a huge variety of things.

Hedgerows, yes hedgerows, might just provide an interesting insight into the art of decision making and developing resilience.

First, the Great Hedge of India. An impenetrable hedgerow 3700km long and 4m tall, built as a customs barrier dividing India to collect salt taxes.

Existing between 1840 – 1879 at its peak it employed 14,000 people.

It was a monumental piece of infrastructure.

However, 100 years later it was lost from memory, with virtually zero physical evidence it ever existed.

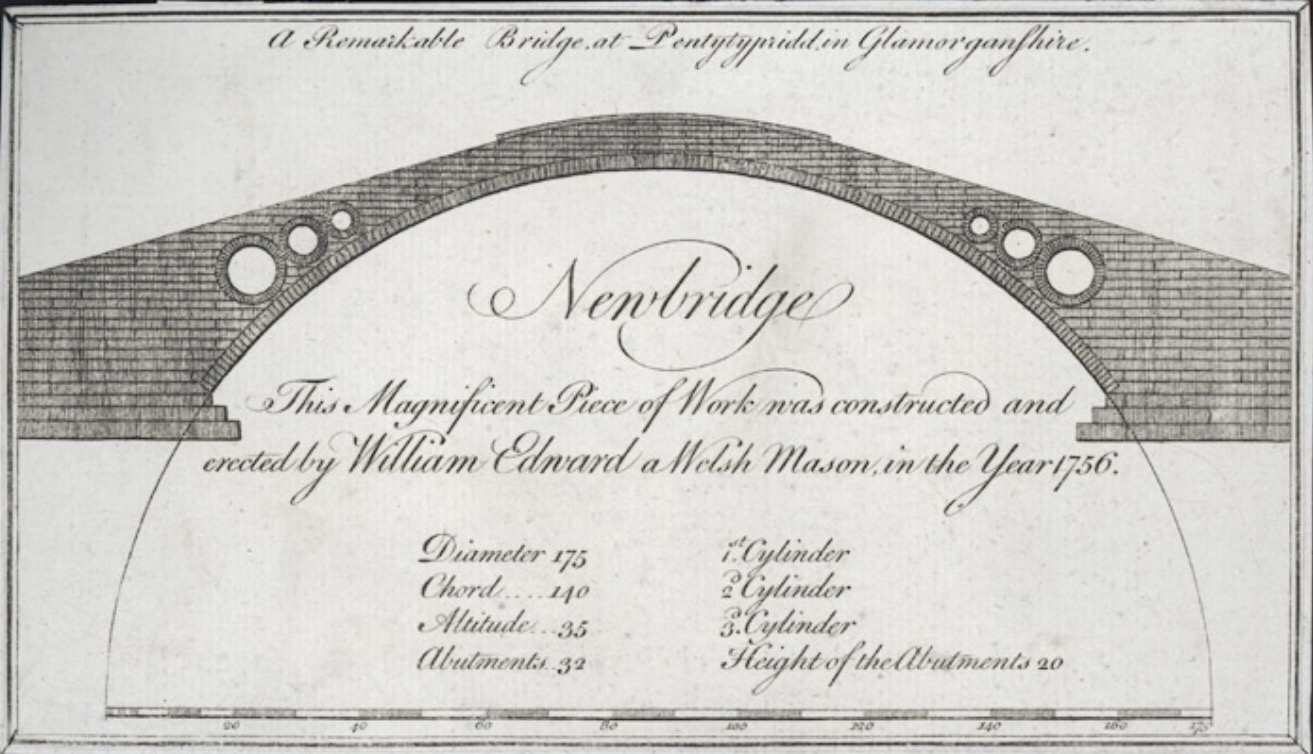

Second, Welsh Farm Hedgerows, Cloddiau. The stone and earth banks topped with trees and bushes that still exist across rural Wales.

Cloddiau have been part of the landscape, for at least 400-500 years and probably longer. Ultimately they are a product of historic local decisions that still play a useful role today.

Something as ordinary as a hedgerows might just give an insight into governance, longevity and community memory.

What is governance?

I like this definition from Fan Yang in Rethinking Governance.

“Governance at its best is not control. It is the collective art of learning how to live together with each other, with place and with the future.”

The article describes different types of governance approaches, including indigenous and western, which interest me in the context of hedgerows.

Indigenous Governance involves things such as the idea that ‘land’ shapes laws, authority comes from relationships and “governance is embedded into daily life and long-term stewardship”.

There are however difficulties in this approach around the ability to operate at scale.

In this description I saw a lot a similarities with the stewardship of a common resource I observed around the Maine Lobster Fishery.

“We are looking after this for our grandchildren…” was a commonly used phrase I wrote about.

Western Governance involves things like legal rights, land as property (rather than a focus of relationships), large scale coordination and provision of infrastructure.

Governance is a thing done by special people, in special places, using special language. Apologies, I’m overplaying it there, but you get my point, it’s not embedded in everyday life.

One area of difficulty for western governance is around ecological stewardship. This struggles in a system that is focussed towards the creation of economic value and growth.

The LinkedIn article by Fan Yang is well worth reading.

The East India Company and the Great Hedge.

The example of the East India Company building a 3700km long customs barrier hedgerow, to impose a salt tax on the local population, feels like it’s got Western Governance written all over it. As well as a few other descriptions.

I’d suggest having a read of the Great Hedge of India by Roy Moxham. At one level this is the story of multiple attempts to find evidence, physical or otherwise, of a massive piece of infrastructure.

There was virtual no trace 100 years after the hedge was abandoned.

This may partly be because a hedgerow will die and decompose, but it might be associated with the nature of the governance.

The creation of the hedgerow wasn’t part of local indigenous decision making and governance. Perhaps this (western) approach to governance helped to erase the memory?

Tir. The story of the Welsh Landscape.

This is another book I highly recommend, written by Carwyn Graves.

The chapter on hedgerows, cloddiau, describes a long association between the landscape, people (who were mostly farmers) and the barriers they built to define different uses for the land.

The principal purpose of these barriers was to stop animals eating the fodder being grown to feed them during the winter, rather than ownership.

A close read of the cloddiau chapter suggests to me a form of indigenous governance. The land defines how things are done, relationships and stewardship of the environment are important drivers of decision making.

Something that is embedded in the day to day activities of local people.

Whilst the current hedgerows / cloddiau might only be 400-500 years old, there’s a strong suggestion that they are based upon much older patterns of land stewardship. Possibly back to the Bronze Age.

That shouts out indigenous wisdom, longevity and a bit of indigenous memory to me.

And when it comes to memory, the fact that these hedgerows remain (even if they are scarce and fragmented), may say something about how indigenous governance can support longevity and resilience?

So, What’s the PONT?

- Governance isn’t new. We’ve been making decisions about our farms, tribes and communities forever.

- Governance doesn’t need to be a special thing, done by special people in special places.

- Maybe a Hedgerow can tell us something about what approach to governance is best for our resilience, longevity and the future?

PS. Thank you to friends who pointed me towards the Great Hedge (Lisa) and Tir (Ena).

Leave a comment